The 14th and the 15th of August is the anniversary of the Partition of India, an event that occurred in 1947 and refers to the splitting of British India into India and Pakistan. As well as affecting India’s borders, the seminal event is often cited as the cause of certain religious and cultural divides.

India and Britain have a complicated history, dating back to the East India Company which was established under Elizabeth I in 1600. It was not until the death of Emperor Aurangzeb and the fall of the Mughal Empire in 1707 that Britain gained a stronger foothold in India, and used their naval fleet to transport more British men over to secure that hold. The foundations of the British Empire are attributed to Warren Hastings, who was appointed the head of the Supreme Council of Bengal in 1772, and Robert Clive, a military man who led a decisive victory over the Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Palashi (anglicised as Plassey) in 1757. Under Hastings’ rule Calcutta was redeveloped and became the capital of British India.

The East India Company fell after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, and India found itself under the control of the crown. It was in 1877 that Queen Victoria added ‘Empress of India’ to her title, and it was during this time that Britain introduced several new modes of transport to the country. India was longing for independence, and this reached its head in the 1900s.

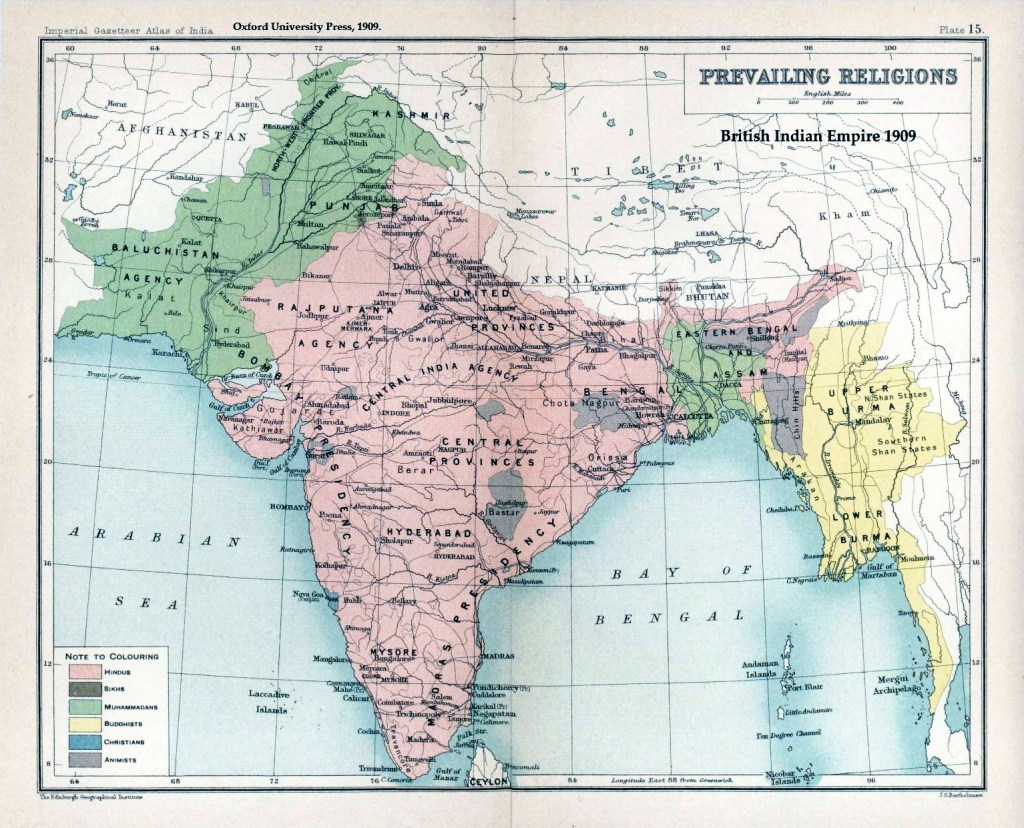

The roots of partition can be traced back to 1905, and the Partition of Bengal. Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, divided Bengal into Western Bengal and Assam, and Bengal. Curzon did this as he believed the large province of Bengal was too large to govern as one. This decision was heavily based on religion, with Muslims dominating Western Bengal and Assam, and Hindus occupying Bengal. This divide, based on religion set precedents for how boundaries would be drawn going forward, and encouraged a nationalist movement in India.

However, decisions-based on religion were rarely based on established, reliable facts, and instead encouraged religious hostility. India itself is a large melting pot of many different cultures and religions, and so drawing borders based on generalisations is viewed today as extremely reductive. At the time though, it took hold, and the two-nation theory began to gain traction, formalised in the creation of the India National Congress Party and the All India Muslim League.

The India National Congress Party was formed in 1885, and the All India Muslim League was formed in 1906, both vying for Indian independence. The All India Muslim League however argued that due to their differing religions, Hindus and Muslims had distinct cultural differences, and therefore, could not coexist in one nation. The All India Muslim League believed that a united India would be majority Hindu, and would therefore overlook the needs of the Muslim population.

In an attempt to try and appease both parties, Britain allowed the people of India to vote in the 1909 local elections, but, they gave Muslim people a separate electorate. This created two separate power structures in the same geographical area, only fuelling the All India Muslim League’s belief that Muslims needed their own independent state. The two-nation theory was something that Muhammed Ali Jinnah continued to champion when he became head of the All India Muslim League in 1913. Under Mahatma Gandhi, the India National Congress Party won the 1937 Indian election, something that only fuelled the All India Muslim League’s initial concerns.

During the Second World War, Churchill worked with Jinnah, who cooperated with the war effort during the Second World War. In return, an agreement was made that the All India Muslim League could secede from an independent India, should the occasion arise. Following World War II, it became obvious to many Britons, bar Winston Churchill, that Indian Independence was inevitable.

Clement Attlee was sworn in as Britain’s Prime Minister in 1945, and was sympathetic towards Indian Independence. In the 1946 elections, the prospect of an independent Pakistan became more of a reality as the All India Muslim League won 87% of Muslim seats, and the Indian National Congress Party won 90% of non-Muslim seats. Jinnah also announced a Direct Action Day, which erupted into violence now known as the 1946 Calcutta riots, beginning on 16th August 1946. With this announcement, Jinnah aimed to encourage strikes and economic shut downs to protest for an independent Muslim state. This violence continued into the next year, and Britain essentially lost control of the situation.

Lord Mountbatten, the Viceroy of India at the time also wanted an independent, but united India, one that would hopefully become a strong ally in future. These bubbling tensions, fuelled by beliefs about the two-nation state continued, and led to the eventual decision to split India into India and West and East Pakistan, a name formed of several different areas:

P = Panjab

A = Afghania

K = Kashmir

I = Indus

S = Sindh

TAN = Balochistan

It was up to the British to adjust the actual borders, with most areas in India opting to either join India or Pakistan. However, the districts of Bengal and Panjab were to be divided based on the density of religious populations, a tactic used to Partition Bengal in 1905. The new map, drawn by Sir Cyril Radcliffe, who had never been to India, was released two days after India and Pakistan became independent, on the 17th of August. This is what prompted mass migration, as some families, quite literally, found themselves on the wrong side of the border. It was this mass migration, an estimated 10 to 12 million people, that prompted religious violence and bloodshed. Although at the time the borders seemed absolute, East Pakistan became Bangladesh in 1971.

Partition explains why some important Sikh locations are now based in modern day Pakistan, such as Guru Nanak’s birthplace. It also explains why the Panjabi language has variations, as there is a version of the language influenced by India, and one by Pakistan.

The event has had a significant impact on popular culture, and is referenced in literature, film and television, including Salman Rushdie’s ‘Midnight’s Children’ and even a Series 11 episode of ‘Doctor Who.’ The ramifications of the widespread suffering caused by the divide are still felt today, and explain certain religious and cultural conflicts within India.

Partition also explains the ongoing Kashmir conflict. Initially, Kashmir was left to decide it’s own future, and at the time, their ruler, Hari Singh decided to bring Kashmir under India’s rule. Singh needed India’s military backing against Pakistani tribal invaders. This led to the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, a conflict that resulted in the drawing of another border, the Line of Control. The Indian Pakistan conflict over Kashmir has peaked and troughed for decades.

It is clear from this alone that Partition still inspires complex debates about religion, culture and identity, communicating that its effects are still keenly felt today.

Thanks for reading!