Everyone knows what birthdays are – they are the anniversary of someone’s birth. A birthday comes around once a year, ie, September 10th, a birthdate, is the complete date, ie, September 10th 1999. Nowadays birthdays are heavily celebrated with cake, with some birthdays carrying more weight and importance than others. But where did these traditions come from? And why do we eat cake?

Going back to ancient Egypt, the Pharoah’s did not celebrate the anniversary of their birth, but the anniversary of their ascension to the throne, which was seen as their ascension into godhood. Greek Historian Herodotus noted in his works that Persians took great pleasure in celebrating their birthdays, and that the rich treated themselves to baked cow, horse or camel. The Romans however did not initially celebrate people, but institutions. So perhaps the anniversary of the founding of a temple, or a university was celebrated. Over time, the Gods associated with the place in question became more directly celebrated, for example, March 1st is known to be the birthday of the God Mars.

As does most things, this changed overtime, as ordinary people began celebrating the anniversary of their birth. Romans believed that every individual had divine nature, and that this aspect of their being needed to be worshipped and respected. For men, this spirit was called the Genius, and for women, Juno. So, on the day of their birth, the Romans would make offerings in the lararium, or the household shrine. This expanded, and birthday parties began to enter the picture.

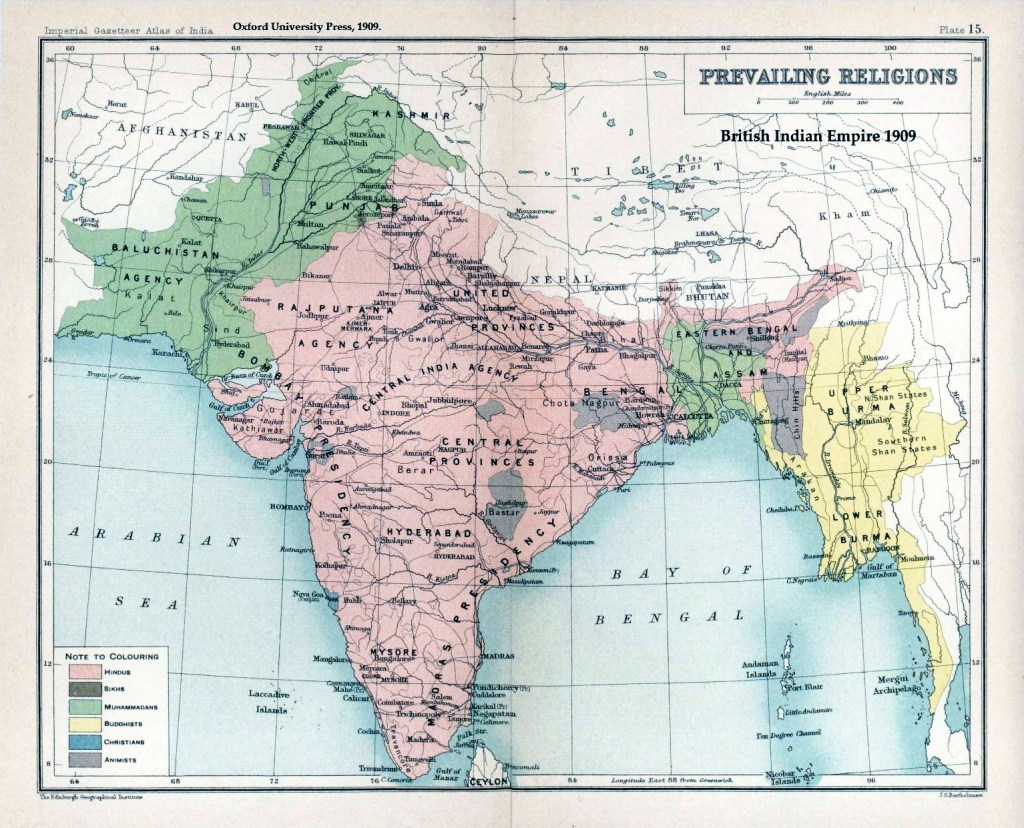

Birthday parties solidified alliances, familial bonds and friendships, and were seen as great social occasions. In 1973, Robin Birley discovered the Vindolanda tablets, the oldest surviving documents in Britain that dated back to Roman times. Transcribed was an invitation to a birthday party. Books were also popular gifts. If a high profile member of society died, their birthday would be celebrated in the following years, which is something that is a popular tradition across the world. Sikh people celebrate the birthdays of the ten Gurus, known as Gurpurb, Hindus also celebrate Ganesha Chaturthi which marks the birthday of Ganesha.

Saint’s days have historically been celebrated, typically on the day of the named saints’ death or martyrdom. During in the Middle Ages, the majority of the population celebrated their saint’s days, which was the saint they were named after. In Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox countries, Saint’s Days were known as name days. The festivities resembled that of a birthday and were celebrated on the day of a saint with the same Christian name as the birthday person. In ‘War and Peace,’ Pierre visits Natasha on her name day at the start of the novel.

During the Middle Ages, it was the nobility that celebrated the anniversary of their own birth, and whilst early Christians regarded birthdays as pagan rituals, nowadays Christians are quite open to the idea. Jehovah’s Witnesses are still sceptical however, citing Christianity’s previous condemnation of birthdays and their potential links to superstitions and magic. Sikhs also do not encourage the celebrations of birthdays, viewing them as superficial festivities. Sikhs instead view the day as an opportunity for spiritual reflection.

The tradition of eating cake dates back to ancient Greece, where offerings of round, moon-shaped cakes with candles were made to honour the goddess Artemis. In Germany, during the 18th century, this tradition continued with Kinderfest, where candles were used to ward off evil spirits who would attempt to steal the children’s souls. It is from here that many of the birthday traditions that we see today originated, and it is estimated that in-between 50 to 100 million birthday cakes are eaten every day!

Some birthdays hold more significance than others, particularly 18 and 21. As you may have guessed, these are the ages where you are legally seen as an adult, also known as ‘coming of age.’

The well known ‘Happy Birthday’ song was written by American sisters Patty and Mildred J Hill, and first appeared in print in 1912. The melody was originally composed with the aim of helping children to learn, with the phrase ‘Good Morning to All’ originally being used.

Happy Birthday everyone!

Thanks for reading!