‘Doctor Who’ showrunners have always championed inclusivity and diversity. Chris Chibnall’s condition of taking over as showrunner was that The Doctor should be a woman, when Steven Moffatt cast Pearl Mackie as Bill, he openly stated that the show should ‘do better’ on the diversity front and Russell T Davies’ most recent run is probably the most inclusive to date, featuring the groundbreaking trans character of Rose Noble and the first ever black incarnation of the Time Lord.

As a viewer, and as a person of colour, the diversity debate is always a tricky one, mainly because, more often than not, those having the debate are not people of colour themselves. So, even though characters with our background, and our stories are being put out there, now more than ever, we are not the ones contributing to it, and therefore can be rendered slightly powerless. I work in the television industry myself, and being the only person of colour in the room can be a burden, and it is difficult to stand up, as the minority, and speak up. We are not always listened to, which quite frankly only heightens the imposter syndrome. I am not saying that only people of colour can write people of colour, but I think it is pretty fair for us to ask to contribute to telling our own stories if the occasion calls for it.

I would say that nowadays there are more people of colour on screen, which is lovely. However, sometimes they work and sometimes they don’t – and they don’t work when it is obvious that they are there to tick a box, or if we are not afforded the same presence and autonomy as Caucasian characters. I am not saying that every person of colour should always be the hero, should never be the underdog and should always be the main character. There has to be equality across all bases, and we are only just getting there now. Equality means that, South Asian actors for example, are not just doctors or corner shop owners. Yes, some South Asians do hold those roles in society, but not all of us do. Some of us do other things, and this should also be represented on screen. Caucasian characters can do or be anything on screen, and people of colour deserve that same equality. Only perpetuating that one idea, that South Asians are only doctors and corner shop owners spreads ignorance, which, as we can see, erupted into violence last summer. We can break stereotypes and encourage equality, by allowing people of colour and characters to wear as many hats as Caucasian people do.

First off, I love ‘Doctor Who’, and I think it does some fantastic work. I recently met Russell T Davies at a press night and clumsily told him that, and then went on to tell him about my love for current companion Belinda. He was a lovely man, who totally understood the burden of being the only person of colour in the TV production office. And whilst I have enjoyed Ncuti Gatwa’s second season, more than his first, it was Varada Sethu’s Belinda Chandra that became the main inspiration for this article.

I had not come across Varada Sethu before her ‘Doctor Who’ appearance, but at the announcement of her casting I was excited. Seeing a South Asian woman in ‘Doctor Who’ every week was genuinely thrilling, and I sometimes could not quite believe it. Sethu has also spoken out admirably about reclaiming her cultural heritage, and the difficulties ethnic minorities face in the industry, all of which I keenly relate to. So, not only was she representing us on screen, but she was also using her influence to do some really important work, and I would like to take a second to thank her for that. However, I feel that Belinda has fallen foul of several person-of-colour pitfalls. But, before we get to her, let’s go back to the beginning and start with the original companion of colour, and absolute icon, Martha Jones.

Freema Agyeman’s casting drew attention, and criticism, as she was dubbed as the first full time black companion. Agyeman herself is half Ghanaian and half Iranian Kurdish. On the surface, I would argue that Martha’s cultural heritage was not as openly discussed as much as Yasmin’s or Belinda’s, and her name on paper does not immediately scream any cultural affiliation like say, Yasmin Khan.

This may be indicative of the time that Martha was created, as following cultural movements like Black Lives Matter, there has been greater discussion about accurately representing all races and cultures on screen. In 2021 Agyeman stated that she could not ‘rationalise’ the racism that she was subjected to at the announcement of her casting. I do wonder what it would have been like for her, even behind the scenes, where decisions about her characters’ story, costume, hair and make-up would have been made.

Whilst nowadays it is more common for shows to create a racially diverse world in which all are accepted, like ‘Bridgerton,’ thankfully, throughout her series Martha’s skin colour was not ignored. In ‘The Shakespeare Code,’ David Tennant’s Tenth Doctor prepares to go swanning around Tudor England, with Martha questioning whether she would be ‘carted off as a slave,’ as she was ‘not exactly white, in case [he] hadn’t noticed.’ Writer Gareth Roberts and RTD should be praised for this frankness. Martha highlights racial inequality by quite literally pointing out the obvious. While the Doctor’s colour-blindness towards Martha is a good thing, he goes a bit too far by not realising, and respecting, her concerns about the environment that he has surprised her with. Martha encourages The Doctor to check his own privilege and ignorance, as of course, being Caucasian male presenting, he is able to move freely and will not be discriminated against in this environment.

Martha’s comment is representative of the person of colour experience. I would argue that we are more hyperaware of our surroundings because of our skin colour. Being in the minority at work makes me hyperaware of how I carry myself, as I can easily attract labels. Standing up for myself, and people of colour, risks the ‘woke’ label, or the ‘playing the race card’ label. In the same way, Martha, being a black woman, like all black women, is at risk of attracting the loud, angry, black woman label. Ncuti Gatwa’s Fifteenth Doctor and Belinda subtly discuss this labelling in 2025’s ‘The Story and the Engine’ with both explaining that, in Lagos and India, they feel fully accepted and embraced for who they are. They do not feel different or reduced to stereotypes. The residents of Lagos and India treat The Doctor and Belinda as one of their ‘own.’

Martha suffers another bout of causal racism when caring for John Smith in ‘Human Nature’ and ‘The Family of Blood,’ with Jeremy Baines implying that her hands are the colour of dirt, hindering her from ever being able to tell if the floor she is scrubbing is ‘clean.’ Martha brushes it off, but shows a bit more bite when dealing with Nurse Redfern, recounting all the bones of the hand.

It is Martha’s unrequited love for the Doctor that receives the greater criticism. Agyeman was placed in the tricky position of trying to win over a universe grieving for Billie Piper’s Rose Tyler, and in pining after The Doctor for thirteen episodes, Martha is immediately written as the other woman. This was never exactly going to make people warm to her, as she is characterised as being second best from the off. Without even realising, or probably intending, the storyline turns into a ‘black woman is second best to white female’ narrative, something that The Doctor does not help. Although he never shows any racism towards Martha, The Doctor’s treatment of her is problematic and speaks to wider ideas of racial inequality.

Instead of embracing Martha as a new friend, like Fifteen embraces Belinda after he loses Ruby, Ten is pretty snappy with Martha, throwing around phrases like ‘well find out!’, ‘not that you’re replacing her’ and ‘just one trip then back home!’ Even in her own flat in episode twelve The Doctor silences her when she asks about The Master, quipping ‘that’s all you need to know.’ He negatively compares Martha to Rose in ‘The Shakespeare Code’, saying ‘Rose would know. Right now, she’d say exactly the right thing.’ He never lets Martha choose where they go, and even takes her to the same places he took Rose, signalling to Martha that she is merely a ‘rebound.’

The Doctor also fails to see Martha, sometimes literally, as explored in ‘Human Nature’ and ‘The Family of Blood.’ Asking her to take care of him in a racist Britain is a pretty tall order, and all she gets is a ‘thank you.’ He later jokes in episode twelve that, wearing a perception filter is like ‘when you fancy someone but they have no idea you exist.’ The Doctor is aware of Martha’s feelings for him, as she tells him in ‘The Family of Blood’ that she loves him ‘to bits.’ In the next series he even brags to Donna that Martha ‘fancied’ him, with Donna responding that she must be ‘mad,’ ‘blind’ and calling her ‘charity Martha.’ This is not Martha Jones’ fault, and it is unfortunate that no one on the production thought that this dynamic is kind of uncomfortable.

On the surface, and in The Doctor’s eyes, she never quite manages to be Rose’s equal, and while this is not racially motivated, on the surface the relationship is unintentionally racially insensitive. The Doctor makes his only companion of colour feel inferior to her white predecessor to the point that she agrees, worrying that she was ‘second best.’ It is only at the end of the season that Martha realises her worth, and capitalises on the agency that she always had, in what I would call the best, and most satisfying, RTD companion exit. Martha had always been capable and clever, more so than Rose, she was training to be a junior doctor after all.

This is a key part of her character, and perhaps unintentionally, she ends up looking after The Doctor on many occasions. She saves him in ‘Smith and Jones’ and ‘42,’ looks after him in ‘Human Nature’ and ‘The Family of Blood,’ supports him with a job in a shop during ‘Blink,’ briefly houses Jack and The Doctor in ‘The Sound of Drums,’ and later nips out for a chip run. Martha seems to be the one making sacrifices for The Doctor, more so than Rose ever did. Yes, Rose did her dinner lady stint, but I would say in Series One Rose rules the roost, her and The Doctor are pretty much equals from the off, and remain so until her departure in ‘Doomsday.’ It is unfortunate that the first black companion does not always get to choose, and puts her wants and needs aside for The Doctor, something that her Caucasian predecessor or successor did not have to do.

It is weirdly meta, and perhaps was intended to reflect the world that we live in. It is a sweeping general statement to say that people of colour are merely tolerated, and it is certainly not true across the board. However, considering the race riots last year, and my own experience, racism and racial ignorance are still very much alive. The Doctor never fully embraces Martha for who she is, and even though he invites her on board, he does so at first with snippiness and restrictions.

Even when Martha is leaving, he interrupts her when she begins explaining her reasoning, asking ‘is this going anywhere?’ Worse, Ten is totally oblivious to his own behaviour, and Martha never calls him out for his poor treatment of her. This would have been particularly empowering, and perhaps would have inspired viewers to call out poor behaviour that they have received. The harmful dynamic that has played out over the series, which is probably reflective of society, is never challenged. When comparing the optics of this relationship to that of Ten and Rose and Ten and Donna, it does not compare well.

Now, I hear someone saying, ‘well Twelve was not very nice to Clara.’ And yes, I would say in Series Eight, at times he was not. But we knew that he ultimately respected her, he listened to her, and asked for her opinion, specifically on whether she believed that he was a good man. Whether or not you agree with The Doctor’s actions in ‘Kill the Moon,’ in his eyes, he was ‘respecting’ her. It is not as clear cut and one sided as the dynamic of Ten and Martha.

After Martha leaves The Doctor, she flourishes. She becomes a doctor, as she always intended, and makes waves at UNIT and Torchwood. This is pretty impressive character development, and from Series Four onwards, she is The Doctor’s equal, and earns the respect she always deserved. Interestingly, as soon as Martha leaves, The Doctor welcomes Astrid with open arms, which is very different to how he initially received Martha.

Martha’s mission at UNIT in Series Four really speaks to me. In conversation with the Doctor, she explains:

‘It’s alright for you, you can just come and go but some of us have got to stay behind. So I’ve got to work from the inside, and by staying inside maybe I stand a chance of making them better.’

Here Martha is referring to UNIT’s values of course, but this is how I personally think of the Film and TV industry. I talk about it more at the conclusion of the article, but my belief is that, as an ethnic minority, if I keep fighting for my place in this industry, I can get to a point where I can affect positive change. I can champion new talent, and champion diversity. For Martha, this is her greater calling. She has experienced a different life with The Doctor, and is now using her experiences to better her world. Martha Jones – a true icon and role model.

Martha’s appearance in ‘The End of Time Part Two’ is a divisive one, most notably for her marriage to Mickey Smith, a union which has of course been subjected to the race debate. Do I think they are together because they are both black? No, I don’t believe RTD thinks that way. People of colour do gravitate to each other, I can attest to that, and they do have a deep, shared experience. Martha and Mickey both were treated as second best, and both had unrequited loves. Perhaps it was simpler and was just easier for the filming schedule. I think it is probably the lack of development that the romance had on screen that jars people, and I will say that I was a bit disappointed that Martha had seemingly ditched her medical career.

So, following Martha and RTD’s exit in 2009, we did not have a full-time companion of colour until Pearl Mackie’s Bill Potts in 2017. Steven Moffat openly searched for a non-white actor for the role, and interestingly, it is not Bill’s race that takes centre stage, but her sexuality. She does come up against racism in ‘Thin Ice,’ prompting Peter Capaldi’s Twelfth Doctor to land a pretty heavy punch. Also, at the start of the episode set in Victorian London, Bill points out that ‘slavery is still a thing,’ which, unlike Ten, Twelve acknowledges. Apart from that it is her sexuality that pops up far more frequently.

Twelve is much more responsive to Bill, than Ten was to Martha. Perhaps this is because Twelve was not grieving, he had processed the loss of River Song. Although Twelve and Bill are not equal in terms of rank, he is tutor, she is student, he never treats her as less than him. Is this reflective of growing sensitivities, or purely character choices? I think Bill is a likeable and fun character, but for me, she fails to leave a big mark because she lacks agency, something which Martha did exercise throughout her tenure.

Most companions do something to save the day during their introductory episode, Rose, Martha, Donna, River and Amy, and although Clara may not explicitly, her echoes do have impact. Even Yaz contributes by driving the crane. Most companions also have some agency in their own exit, Rose chooses to stay behind and help Ten, Martha leaves, Donna attempts to kill Davros causing him to trigger the meta crisis within her, Amy chooses Rory and Clara chooses to take Rigsy’s tattoo. Bill’s cyber exit, whilst no doubt shocking viewing, is forced upon her, and never quite had the emotional mic drop that other companion exits had because it was not character driven.

Bill does challenge The Doctor, and supports him, but in terms of character defining acts, I can only think of a couple from The Monks saga. In Series Ten’s two part, albeit brilliant finale, Bill’s primary function is to first be turned into a Cyberman. She is definitely generally liked by the fanbase, I would argue more so than Martha, but neither of them ever top any companion polls like Sarah Jane, Rose or Donna.

One interesting thing to note, is that Bill is very normal. Like Martha, Yaz and Belinda, Bill does not have any mystery box narrative surrounding her, and does not become superhuman like Rose, Donna, Clara or, in part, Ruby. An interesting coincidence.

Next, we get Yasmin Khan in 2018, the first televised companion of South Asian descent. I’ll admit, I do find Yaz tricky. First off, props to Chris Chibnall for crafting a consistent cultural heritage for her. Her name implies that she is Pakistani Muslim, a note that is supported and commented on throughout Series Eleven.

We hear about her experiences as a person of colour in ‘Rosa,’ as she and Ryan discuss their experiences of racism. Top marks here Chibnall. Using your characters to contextualise/explain the wider themes of the story while making them more relatable, and developing said characters’ relationships at the same time? That is the mark of good representation.

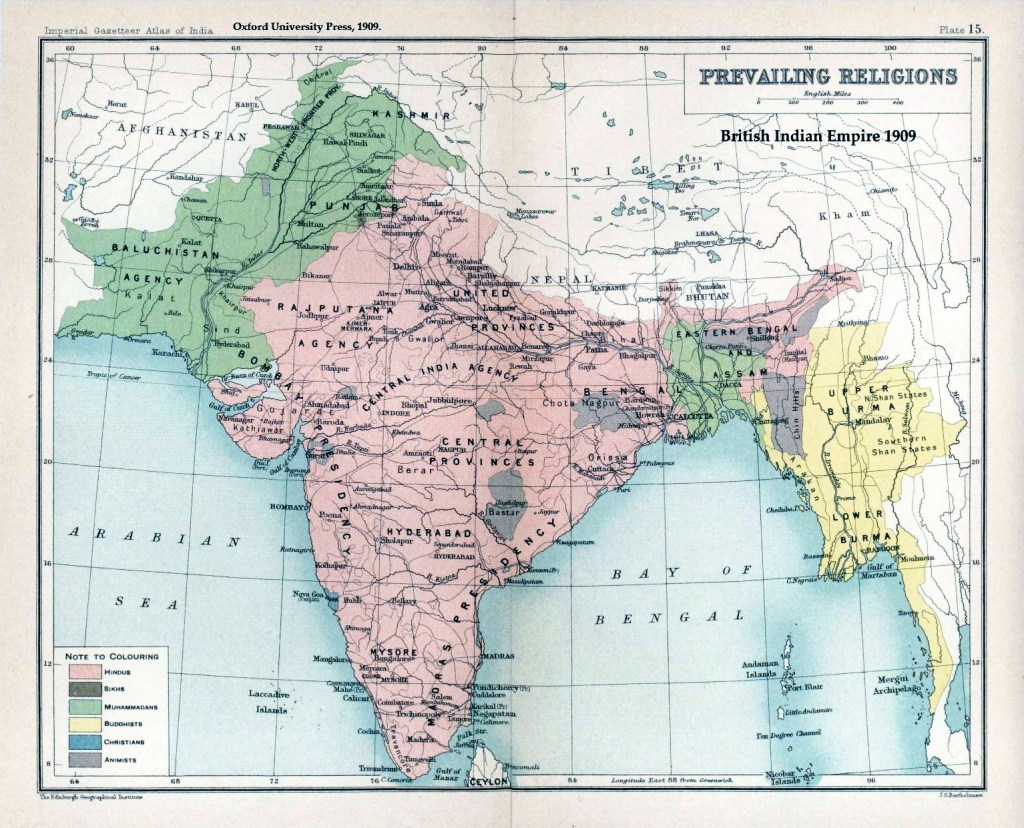

In ‘Arachnids in the UK,’ we meet Yaz’s family, their names all consistent with her established cultural heritage. In ‘Demons of the Punjab’ The Doctor takes the team to India at Yaz’s request, so that she can learn more about her family. For me, as a Sikh Panjabi, the idea of an episode set in India was very exciting, and it felt even more meaningful that it was written by South Asian writer, Vinay Patel. Regardless of what you think of his tenure, I do commend Chibnall for encouraging greater diversity behind the camera.

In my analysis of Yasmin you may think that I am implying that a character’s cultural heritage needs to be mentioned in every single episode, but this not the case. I believe that it enriches a character, and if touched upon, can open a plethora of new stories, as ‘Demons of the Punjab’ and ‘The Story and the Engine’ prove. As Meera Syal said in her BAFTA Fellowship acceptance speech, we do have some great stories, people just need to listen. So, from the cultural perspective side, Chibnall did some good work with Yasmin, especially in her first series. It is just a shame though, that the character has received very mixed reviews, and I personally find her quite unmemorable.

Apart from ‘Demons of the Panjab,’ I do not feel that Yaz contributed much to the series. She did not have an arc like Graham and Ryan in Series 11, so, although within the show she is never considered by The Doctor to be second best like Martha, to the viewer, she was frequently an afterthought. I cannot recall any significant thing she did in Series 11, bar driving the aforementioned crane and kicking the Pting in ‘The Tsuranga Conundrum.’ This is where the tickbox debate rears its ugly head, as, if Yasmin’s character does not impact that much on plot, then we have to ask, why is she there? To enrich the diversity optics on screen? In terms of big, series or universe defining moments, Rose absorbed the Time Vortex, Martha walked the Earth, Clara jumps into The Doctor’s time stream and Bill gifted the planet to The Monks. Nothing of this much note springs to mind for Yaz. She is currently faring less well than Bill. Yaz does assist the team, and is helpful, but this is something all companions do. It is harsh to say but it is almost the bare minimum. In my opinion Yaz fills the stock companion role more than any other discussed in this list.

Also, Yaz is incredibly humourless. When people think of comedic companions they probably think of Donna and Bill, but they all have their moments. Martha saying ‘we’re on the bloody Moon’ in her first episode, Rose being comedically camp when possessed by Cassandra and Clara gleefully teases a relationship with Jane Austen. Take Captain Jack’s surprise return in ‘Fugitive of the Judoon,’ for example. He had more charisma and humour than Yasmin, Ryan and Graham put together.

Her role kind of grows in later seasons, but more due to her longevity, not because she really does anything. Thirteen confides in her in Series Twelve, and Graham tells us that Yasmin is amazing, without us really seeing it. She springs Dan from Karvanista’s trap in ‘The Halloween Apocalypse,’ but, even after all these years, in ‘Flux,’ Thirteen draws back, becomes more secretive, asking Yasmin: ‘does everything have to be a discussion? Go on. In.’ Pretty hard to influence the narrative when you are being told to shut up and move. Martha’s ears must have been burning.

A recurring joke within the fanbase throughout Yasmin’s run was that she would frequently pick up and drop the idea of being a police officer. Her exclamation in ‘Fugitive of the Judoon’ that she is a ‘police officer’ drew more laughs than cheers, especially because she then claimed to speak the Judoon’s ‘language.’ To her credit, we do see some police skills spring into action in ‘It Takes You Away’ and ‘Village of the Angels,’ but something that was marketed as key to her character does fade away pretty quickly.

Martha and Belinda were more consistent on the job front. It was well tied to their character. We see her fix Hath Peck’s arm, and we see Belinda administer alien IV lines in her debut episode. Ok granted, Martha later goes freelance in a move that I am still not sold on, but I will let that one-minute scene slide.

Perhaps now Yasmin is more remembered for her near romantic relationship with The Doctor. While Bill’s sexuality is fully realised and explored, she has a love interest that develops over time and reaches a conclusion, Yasmin really does not have much to go on. It could have been an interesting story, and in RTD’s most recent episode ‘The Reality War’ he does confirm that it was really a thing… but I think the reception from the fanbase is pretty lukewarm as people just assume it was tacked on for the last three episodes, and wished into existence by the fans themselves.

So how does Yasmin fare overall? Yasmin’s cultural background is well utilised, as epitomised by ‘Demons of the Panjab.’ This episode is a good example of representation, and supports the idea that, when you take note of someone’s cultural heritage, it opens doors for stories. It is just a shame that her overall blandness and half-baked love for The Doctor land her on the lower end of companion polls.

Next, we get RTD with Belinda Chandra in 2025. In my mind, she manages to take steps forward, but also backwards. Now, there is probably a Keralan woman out there called Belinda, but Varada Sethu is South Indian, she does have a cultural background that can be drawn from. My question is, why not capitalise on that and choose a South Indian name, for a companion who is quite openly South Indian? She longs to take Poppy to Kerala, her parents are called Lakshmi and Hari.

Chandra is also more commonly associated with North India, as demonstrated by Panjabi character Rani Chandra in ‘The Sarah Jane Adventures.’ Belinda is a South Indian woman with an Italian and Spanish first name, and North Indian surname. It’s not all quite adding up. If this cultural incoherence is not going to be explained at all, then perhaps the writers should just play it safe, to avoid people like me writing pieces like this. Yasmin Khan is probably the most Pakistani Muslim female name you can find, there’s a reason both names pop up on television frequently.

There is a moment in her first episode where Belinda is referred to as ‘Linda’ by a housemate, and she swiftly corrects him. People get my name wrong all the time, and although people get names wrong in all cultures all of the time, it is very common for people of colour, and leads to people of colour changing their names, or anglicising them. I am Harpal, but I go by Harps. Varada goes by V, character Darwish Zubair Ismail Gani from ‘Parks and Recreations’ goes by Tom Haverford. Sethu recently spoke about the correct pronunciation of her name on BBC Asian Network, and how she is reclaiming it, like so many other South Asians. If Belinda had a South Indian first name, this moment would have acknowledged one of the microaggressions that people of colour experience, giving it a greater cultural and societal relevance. Interestingly Belinda is happy with The Doctor calling her Bel, something he does without her permission.

Maybe Belinda is Indian Christian. Indian Christians make up two percent of the Indian population, and a significant population is concentrated in the South, totalling five percent. Perhaps that is the answer, Belinda is Indian Christian… but her connection to Kerala confuses with her North Indian surname. Hey, if Belinda is Indian Christian, then explain it, it could make a good story, there was space for it in ‘The Story and The Engine.’ In film and TV, there are probably more Asian characters with non-Asian names due to colourblind casting. Chibnall had Mitch in ‘Resolution.’ Colourblind casting is a good thing to a point, but it works both ways. If you ignore somebody’s skin colour fully, you ignore a key component of their identity in the process. It’s steps forwards and steps backwards.

You are probably wondering why I get so bogged down with names. Well, there have probably been a million characters named Belinda on screen. Probably loads named Bill and Martha too. A companion of colour presents the opportunity for a new name to enter the Whoniverse lexicon. It’s a chance to hear different names on screen and a chance to normalise them. Out of four full time female companions of colour, only one has a name that reflects their cultural heritage. If you read the names in a list, you would probably only assume that one is a person of colour: Rose, Martha, Donna, Amy, Clara, Bill, Yasmin, Ruby and Belinda. We have decent visual representation, but surely it enhances this representation even more if the names follow suit. As we can see, there is clear imbalance.

If we work backwards, in her last episode, Belinda longs to show Poppy Kerala. So, Belinda is clearly in touch with her cultural heritage, specifically Kerala, which is nice to see. However, this specificity, that Yasmin had, wavers. In episode seven, Belinda refers to her mother as ‘amma,’ meaning mother in several South Indian languages. In episode five, Sethu refers to her nan as… nan. This seems inconsistent. Belinda states that her nan would take her to ‘India whenever she could.’ Perhaps Belinda’s nan took her all over the country, but, surely it makes more sense to take Belinda to Kerala, as, as, described in episode eight, this is something she wants to do for Poppy. It would only strengthen her connection to Kerala and explain why she wants to take Poppy there, she is following some sort of family tradition.

RTD has written two companions of colour. Belinda is embraced by The Doctor, unlike Martha, and has a stronger connection to her cultural heritage, which enriches and adds dimensions to her character. It also strengthens her understanding of The Doctor in this body, something we see in ‘The Story and The Engine.’ Belinda is also the second woman of colour to be an NHS worker. This kind of leads into what I mentioned earlier, stereotypes are ok in moderation, as long as you tell people that it’s not ALL that we do. So maybe Belinda should have been something totally different, like a CEO. That would be very cool!

I am more critical of Belinda’s NHS hero status more than Martha, because, as the series progresses, Belinda gets more and more detached from this job. Part of Martha’s exit was her desire to finish her medical training, something so essential to her that it informs all her later appearances, it is not abandoned like Belinda’s status as a nurse or Yaz’s as a police officer. In episode six, Belinda calls The Doctor wonderful after she sees him torture someone. She is a nurse, why is she not more horrified by this? After saving the universe in episode eight, she is also happy to fly around the universe with The Doctor and happy, seemingly abandoning her one motivation all series – to get home for her shift.

It’s in the two-part finale that Belinda really suffers. Normally, companions play a pivotal role in the finale. Ruby and her mother defeat Sutekh, Amy Pond brings The Doctor back at her wedding, Martha’s actions restore The Doctor. Belinda is sidelined more than any other companion in her own series, even beating Yasmin, and ends up playing second fiddle to her Caucasian predecessor, Ruby in an RTD repeat.

So, in episode seven Belinda is reduced to the dutiful wife as she is trapped in Conrad’s Wish World. It is supposed to be unsettling, and it is supposed to feel abnormal, and not true to either The Doctor or Belinda. I do not have an issue with this, as this is the storyline. The whole point is that it is meant to set alarm bells off for the audience. The failure is, is that in episode eight, she fully becomes the satire that we were meant to be horrified by, and goes all out to protect a daughter she was given without her consent, and nearly hinders the entire rescue mission in favour said daughter. It is a lot to ask the audience to be willing to sacrifice the universe and a Doctor for a child that is very new to the narrative.

Worse still, after The Rani and Omega are defeated, Belinda is willing to travel the stars with The Doctor and Poppy, abandoning her one motivation across the whole series – to go home for her shift and to the parents that she loves so much. She also becomes strangely and unsettlingly saccharine. Very Stepford wife.

Hey, if Belinda always dreamed of having a child, then fair play. It probably would have been quite moving to see The Doctor sacrifice himself for the dreams of his companion. But satirising her passive role in ‘Wish World,’ and showing her growing distress at it, cue her screaming in a forest, and then making it real extinguishes the character that everybody loved in her debut. She becomes the character that she tried to escape as a teenager, the woman that Alan would have forced upon her.

The fact that she sits tight in a box for most of episode eight is also upsetting, as Ruby, who is not this series’ main companion, does all the heavily lifting. Any agency Belinda had vanishes, as well as her concept of consent. She did not choose to have this child, and yet is willing to pledge her life to her at the expense of the universe. She is happy for The Doctor to fight in the battle to save Poppy, contradicting her dialogue in ‘The Robot Revolution’ that she can fight her own battles. It makes far more sense for Poppy to be the daughter of The Doctor and Ruby, as Ruby actually has memories of her.

From what I can see from reviews and vlogs online, the conclusion to Belinda’s character arc generally has been poorly received. I have seen a lot of content makers saying that Belinda in episodes one to three was winning, and after that, she just goes downhill. It is a real shame, that Belinda as a companion is one of the least liked, with people arguing that she was ‘wasted’ and ‘mistreated.’

Now obviously this dislike and disappointment of her character is not related to Belinda’s ethnicity, it is down to the writing of her character arc, much like Martha. However, it would be nice to have a POC (person of colour) companion celebrated in full by the fanbase, otherwise people of colour in the show just get forgotten in favour of Rose’s, or Donna’s or Clara’s.

What makes it worse is that Martha and Belinda both end up playing second fiddle to their Caucasian predecessors. Martha does so because The Doctor constantly compares her to Rose, Belinda does so because the narrative compels her. As I said before, I am not saying that all companions of colour have to be heroes, but when they are SO few and far between, it is frustrating that when we get one, they never really have the opportunity to shine. They are underserved by the narrative, or The Doctor. Bill Potts probably fairs the best, she is liked by The Doctor, and generally praised by the audience. Martha, Yasmin and Belinda have received much more mixed reviews.

Archie Panjabi’s lack of screen time in the finale as The Rani also stings. She too is sidelined in favour of her Caucasian predecessor, Anita Dobson’s Mrs Flood, who does not contribute anything to the episode, or the previous episode. I was SO excited to see British Asian icon Archie Panjabi in the show, especially playing an alien Time Lady with a Sanskrit name. But alas, she is unceremoniously eaten. The most prominent, South Asian female villain in the whole of the show’s history, eaten. Both South Asian women in ‘The Reality War’ fare pretty terribly.

Maybe all of these women fare better than Naoki Mori’s Toshiko Sato of ‘Torchwood.’ Toshiko is the stereotypical, quiet, nerdy Asian girl, who for most of the first season is separate from the group and almost ostracised. She does more in Series Two, but is still a walking tragedy. She also pines after a Caucasian lead who barely registers, Burn Gorman’s Owen Harper. Doctor and Martha parallels?

I am probably going to be criticised for drawing comparisons. Hey, Bill is one parent down, as is Rose and Clara, Yasmin has a sibling as Martha does, all companions have similarities. But I would argue that the companions of colour have MORE similarities than their Caucasian counterparts. For example, all of them work in the public service sector. Martha the doctor, Bill the canteen worker, Yasmin the police officer and Belinda the nurse. It is common that ethnic minorities do enter into these sectors, which probably is part of the reason that there are fewer working in the creative industries.

The reason that these discussions matter is that, at the end of the day, people of colour, especially women of colour, come under so much scrutiny. They have to contend with sexism AND racism.

I will say, as a minority at work, I do feel that there is more weight on my shoulders to represent, and Sethu recently opined that ethnic minorities feel extra pressure to succeed. If I fail at something, as the only person of colour in the office, I feel as though I am not just letting myself down, but people of colour down as well, as I am the only one there. I am everybody else’s only example of a person of colour in that space, at that time – I end up being the one speaking for all of us. Just as Martha, Bill, Yasmin and Belinda have. It is immense pressure for them, as they are on television. When Caucasian character’s faulter, like Bruno Langley’s Adam Mitchell, I would argue that the impact is not as great, as we have every Caucasian Doctor to be heroic. ‘Adam was terrible but at least we have…’ then we can run off a list. When she arrived, Martha just had Martha. And as society has shown us, particularly with the race riots of 2024, some people in society paint people of colour with the same ignorant, racist brush.

So, when crafting diverse characters, what is the answer? If it is going to be done, then it has to be done properly, for sure, but maybe, no matter what is done, the show cannot win. In ‘Doctor Who’ definite strides have been made, but considering the cultural work done by shows like ‘Bridgerton’ and ‘EastEnders’ in crafting compelling characters who are enriched by their cultural heritage, surely a beloved companion of colour that is the whole package must be on the horizon somewhere in the future.

Thanks for reading!